英서펜타인 큐레이터들은 예술가가 아닌 생태학자·게이머와 논다

-

기사 스크랩

-

공유

-

댓글

-

클린뷰

-

프린트

[arte]에이드리언 청의 아트 살롱

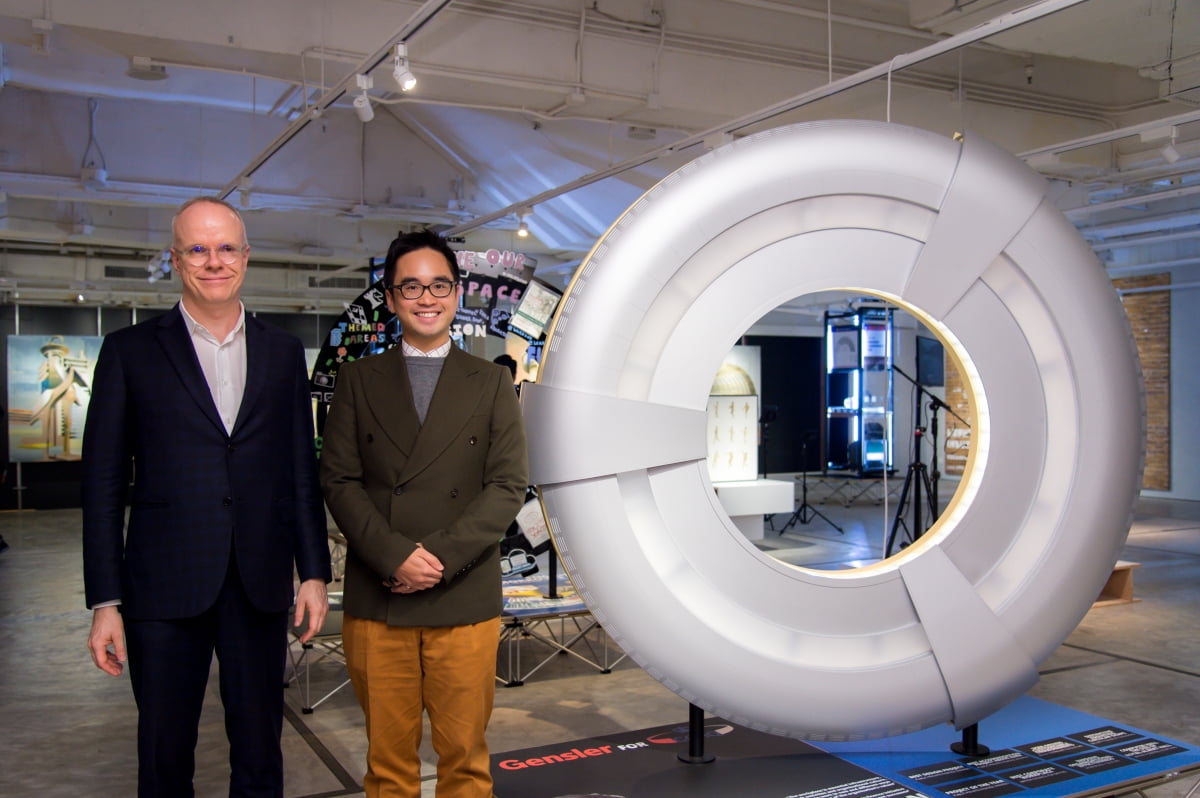

영국 서펜타인갤러리 예술감독

한스 울리히 오브리스트가 말하는

<21세기의 미술관>이 가야 할 길

Hans Ulrich Obrist : Museums in the 21st Century

영국 서펜타인갤러리 예술감독

한스 울리히 오브리스트가 말하는

<21세기의 미술관>이 가야 할 길

Hans Ulrich Obrist : Museums in the 21st Century

안녕하세요. 아르떼 독자 여러분, 에이드리언 청입니다.

오늘은 세계에서 가장 영향력 있는 큐레이터 중 한 명인 한스 울리히 오브리스트 서펜타인갤러리 예술감독의 생각을 공유하고자 합니다. 오브리스트는 예술에 대한 끊임없는 호기심과 헌신으로 현대 미술계의 새로운 길을 개척해 왔습니다. 수많은 획기적인 전시회를 기획했고, 영향력 있는 예술가 및 사상가들과 대화도 이끌어 왔습니다. 존경받는 큐레이터이자 미술 평론가인 오브리스트는 전문성을 바탕으로 한 예리한 안목으로 미술계에서 신뢰받고 있습니다. 이번 에세이에선 기술과 박물관 시스템의 미래에 대한 그의 최신 연구 결과를 다뤄봅니다.

나는 스위스 생갈렌에서 공부할 때 중고품 가게에서 독일 미술사학자 알렉산더 도너의 책 <예술 너머의 길(The Way Beyond Art)>과 처음 만났다. 그리고 이 책을 족히 50번은 읽었다. 도너는 하노버의 란데스미술관을 운영하다 나치를 피해 미국으로 이주한 인물이다. 그는 엘 리시츠키에게서 영감을 받아 박물관을 ‘실험을 위한 곳’, ‘지식 쇼를 위한 실험실’, ‘미래를 보여주는 장소'라고 주장했다.

도너 외에도 에두아르 글리상은 내 인생에 최고로 중요한 영향을 끼친 인물이다. 그는 전시와 박물관에 대한 나의 생각을 완전히 바꿔놓았다. 그는 박물관이 흔히 하는 것처럼 기록물을 상품화하지 않고, 현재의 수집품을 모으고 육성하고 지원하는 기관을 상상했다. 그는 기존의 상식을 뒤집고 박물관을 전 세계의 모든 문화와 상상력이 서로 만나고 들을 수 있는 ‘유토피아적 장소’로 여겼다.

글리상이 주장했던 또 다른 개념은 ‘군도’다. 지리학에서 군도는 한 무리를 이루고 있는 여러 섬을 의미한다. 그는 이 모든 섬에 각각의 문화가 존재한다고 생각했고, 이 개념을 박물관에 적용했다. 박물관에서 이뤄지는 모든 전시를 각 섬들 간의 문화적 교류를 통해 만들어진 새로운 군도와 같다고 여긴 것이다. 즉, 그의 개념 속 군도는 변한다. 어떻게 교류하냐에 따라 정체성이 고정되어 있지 않다. 또 각 섬들이 가진 정체성은 교류를 통해 변화하지만 희석되지는 않는다.

글리상이 말했듯 대형 박물관은 문화적 통합을 위해 노력할 필요가 없다. 박물관에 오직 필요한 것은 전통과 관점 사이의 상호 네트워크다. 박물관은 지금 존재하는 것을 요약하는 곳이 되어서도 안 된다. 우리가 아직 모르는 것을 탐구하는 곳이어야만 한다.

또 다른 중요한 주제는 ‘느린 프로그래밍’이다. ‘우리가 하는 일의 영향을 어떻게 다시 생각할 수 있을까?’, ‘우리의 일이 환경에 미치는 영향을 어떻게 줄일 수 있을까?’ 이런 질문에 답하는 과정을 겪으며 우리는 세상에 기여할 수 있다고 생각한다. 또 박물관은 다른 조직, 생태 기관, 기업, 브랜드와 함께 연합해 이런 질문에 대해 고민해야 한다. 국경의 경계는 필요없는 장애물일 뿐이다.

예술가들은 항상 사람들에게 ‘경계를 넘어라’라고 가르쳐 왔다. 미국의 시인 알렉시스 폴린 검스는 '우리는 이제 서로 소통하는 존재다. 환경을 지배하는 것이 아니라 환경과 교감할 수 있는 방식으로 사고 패턴과 스토리텔링을 배워야 한다'고 말한 것처럼 말이다. 우리는 인간과 환경이 서로 연결되어 있다고 여겨야 한다.

그래서 우리는 지식을 모으는 것에 대한 두려움을 이겨내고 배움의 과정을 시작해야 한다. 박물관은 경직된 지식의 장벽을 허물어야 한다. 박물관의 각 부서 간, 또 박물관과 외부 세계 사이의 벽을 허무는 것을 의미하기도 한다.

내가 2015년에 발간한 책 <Extreme Present>에서 정의내린 박물관의 의미를 실현하기 위해 나는 건축가이자 도시학자로 활동하는 세드릭 프라이스에게 눈을 돌렸다. 그리고 그가 작성한 강의용 메모 하나를 발견했다. 그가 적은 글은 실현되지 못한 프로젝트인 ‘Fun Palace’에서 영감을 받은 것이었는데, 이는 그가 1960년대 초 ‘연극의 선구자’ 조안 리틀우드와 함께 런던 이스트엔드를 위해 추진한 프로젝트였다.

그가 적은 메모엔 『21세기의 예술 기관은 빠르게 변화하기 위해, 또 그 안에서 집중적 수확을 거두기 위해 ‘계산된 불확실함’과 ‘의식적인 불완전함'을 활용할 것이다』라는 내용이 적혀 있었다. 이 대목을 예술가를 위한 지속적인 지원 구조를 만드는 것에 대입해보면 어느 때보다 적절하게 들어맞는다.

오늘날 박물관의 발전을 이해하고 새로운 관객을 연결하는 가장 중요한 도구 중 하나는 바로 기술이다. 나는 항상 예술과 기술은 하나라고 생각하는 것이 중요하다고 주장해 왔다. 이 목표는 큐레이터로서 내가 이루고 싶은 최우선 과제이기도 하다. 그래서 난 매일 새로운 기술을 최대한 많이 배우기 위해 치밀한 계획을 세웠다.

가장 처음으로는 팀 버너스 리와 '월드와이드웹(www)'에 대해 대화를 나눴다. 그 이후 나는 다양한 기술 분야의 선구자들과 여러 이야기를 나누며 예술과 기술이 어떻게 함께 발전하고 기능하는지에 관심을 가졌다. 새로운 기술이 빠르게 발전함에 따라 나의 목표도 더욱 커지고 있다.

기술은 변화의 주요 매개체임이 분명하다. 1989년 버너스 리는 월드와이드웹을 발명했고, 이는 예술뿐만 아니라 사회의 모든 측면에 많은 것을 변화시켰다. 지난 10년간 서펜타인에서는 예술가와 기술을 결합하는 새로운 실험을 시작했다. 5명의 큐레이터와 1명의 최고 기술 책임자로 구성된 전담 부서를 만들고 비디오 게임 전시회를 열기도 했다. 오늘날 비디오 게임은 음악과 영화를 합친 것보다 더 큰 분야로 자리잡았다. 많은 예술가들이 비디오 게임이라는 분야에서 작업을 이어나가고 있다.

또한 예술 기관에서 환경 문제를 해결하는 것도 매우 중요해졌다. 나는 아티스트 구스타프 메츠거와의 대화에서 영감을 얻어 서펜타인에 생태학 큐레이터를 임명하고 환경을 전담하는 부서를 만들었다. 현재 서펜타인의 많은 프로젝트는 지속 가능성, 환경, 멸종 위기 등을 다루고 있다.

단순 전시를 넘어 생각의 범위를 넓히며 나는 브라질 출신의 이탈리아 건축가 리나 보 바르디가 남긴 말인 "내부는 외부에 있다"의 의미를 깨달았다. 박물관은 문 뒤에 있는 전시 공간에서 예술을 보여주는 데 그치지 않고 예술과 함께 사회 속으로 들어가는 것이 매우 중요하다. 매년 서펜타인에 짓는 파빌리온은 공공미술처럼 문이 없고 공원 안에 있다. 방문객들은 이 파빌리온을 체험할 수 있고, 종종 우연히 들르기도 한다.

가장 최근엔 <월드빌딩>이라는 전시회를 기획했다. 줄리아 스토섹 컬렉션에서 열린 디지털 시대의 게임과 예술이라는 전시회를 기획했는데, 이 전시회는 ‘비디오 게임의 보급’이라는 아이디어에서 시작했다. 오늘날 전 세계 인구의 3분의 1이 넘는 약 30억 명이 매년 비디오 게임을 즐긴다. 과거의 틈새시장이 현대에 와서는 가장 큰 유행으로 떠오른 것이다.

많은 사람들이 각자의 게임 세계에서 매일 몇 시간씩을 보낸다. 비디오 게임은 20세기에 영화가, 19세기에 소설이 했던 역할을 하고 있음이 분명하다. 이 전시에서는 단일 채널 비디오 작품부터 현장 중심의 상호작용 몰입형 작업에 이르기까지 예술가들이 비디오 게임과 상호작용하며 이를 예술의 한 형태로 만들어낸 다양한 방식을 조명했다.

이 전시회는 게임 제작이 새로운 세계관을 만들 수 있다는 점을 강조했다. 게임 세계 안에서 이용자가 자신만의 규칙을 설정하고, 주변 환경, 시스템을 만들고 바꾸며, 새로운 세상을 창조할 수 있기 때문이다.

아티스트 이안 쳉이 자주 말했듯, 예술의 중심에는 세계가 무엇인지 이해하고자 하는 열망이 존재한다. 이제 그 어느 때보다 기존의 세계를 계승하고 그 안에서 살아가는 것이 아니라, 새로운 세계를 창조할 수 있는 주체성을 소유하는 것이 예술가의 꿈이 됐다.

이번 전시를 준비하며 펼친 연구를 통해 예술에서 비디오 게임의 중요성이 점점 더 커질 것이라는 것을 직감했다. 끊임없이 진화하는 비디오 게임의 역할과 함께 전시와 박물관이 어떻게 변화하고 발전하는지를 지켜보는 것도 흥미로울 것이다.

/한스 울리히 오브리스트·더 서펜타인 갤러리 예술감독

[칼럼 원문]

Adrian’s Intro :

It is with great pleasure that I introduce to you one of the most influential and visionary curators of our time, Hans Ulrich Obrist. With an insatiable curiosity and an unwavering dedication to the arts, Obrist has carved a remarkable path, leaving an indelible mark on the contemporary art landscape. Throughout his illustrious career, Obrist has curated numerous groundbreaking exhibitions and has engaged in thought-provoking conversations with some of the most influential artists and thinkers of our time.

As an esteemed curator and art critic, Obrist's expertise and keen eye for innovation have made him a trusted voice in the art world. This short essay sheds light on the new findings of Hans’ latest research into the relationship between technology and the future of the museum system.

To think about the development of museums and institutions today, I believe we should be considering generosity. It’s important to come up with new models of museums as batteries of imagination, to understand how one can effect change and introduce new ideas. When I was studying in St. Gallen, Switzerland, I found a book in a thrift store by the German art historian Alexander Dorner, <The Way Beyond ‘Art’>.

Dorner had run the Landesmuseum Hannover and emigrated to the US to flee the Nazis. I probably read this book fifty times. He was inspired by El Lissitzky and believed the museum was for experimentation, a laboratory for interdisciplinary shows, for displaying futures.

Besides Dorner, Édouard Glissant has certainly been the most important influence in my life and completed changed the way that I think about exhibitions and museums. Glissant believed in a museum that would not only point at urgencies but also find agency to respond to these urgencies. He imagined an institution that would not commodify archives, as museums often do, but would gather and nurture and support archives of the present. He imagined the museum as a quivering place that transcends established systems of thought and looks to the utopian point where all the world’s cultures and imaginations can meet and hear one another.

Another of Glissant’s concepts that became important to me was the archipelago. Big museums are like continents, in a way. The archipelago of his Antillean geography is, by contrast, an island group with no centre—a string of islands and cultures. That notion can be directly applied to the museum. Exhibitions can be conceived as archipelagos, self-organised, with exchanges between them. Archipelagos make it possible to say that no person’s identity, and no collective identity, is fixed, once and for all. It changes through exchanges, but without being diluted. Big museums have, as Glissant told me, always tried to fashion a synthesis, but he said we don’t need that. What we need is a network of interrelationships between traditions and perspectives. A museum shouldn’t be about the recapitulation of something that exists in an obvious way. It should be about the quest for something we don’t know yet.

Another important topic is slow programming. How can we rethink the impact of what we do? How can we reduce the ecological impact of our work? In responding to the question of ecology, we can hopefully make a contribution. And that has to do with new alliances—not just with other museums, but with other organisations, ecological institutions, companies, and brands. Borders are the main obstacle to such alliances.

Artists have always taught us to cross these borders. We have to go beyond the fear of pooling knowledge and embark on a process of unlearning. American poet Alexis Pauline Gumbs stated that ‘We have the opportunity now, as a species fully in touch with each other (think social media), to unlearn and relearn our own patterns of thinking and storytelling in a way that allows us to be actually in communion with our environment as opposed to a dominating…separation from the environment.’ This leads us back to Glissant—the need to surrender to the idea of being related to one another and to the environment. Museums have to unmake the walls and separations of the current world and its rigid and specialised silos of knowledge. This also means breaking down the walls between museum departments, and between the museum and the outside world.

In attempting to reach a definition of the term ‘museum’ in the extreme present, I also turn to the architect and urbanist Cedric Price. I found the note that he gave me for a lecture, which was inspired by The Fun Palace, the unrealised project he developed in the early 1960s with theatre pioneer Joan Littlewood, for London’s East End. The note said, ‘The twenty- first-century art institution will utilise calculated uncertainty and conscious incompleteness to produce a catalyst for invigorating change whilst always producing the harvest of the quiet eye.’ These words feel as relevant as ever, especially when combined with the desire to create an ongoing support structure for artists.

Today, one of the most important lenses through which to understand the development of the museum and connect new audiences is through technology. I believe that it is important to think about art and technology together. This question has continued to be a curatorial priority for me, so I began to map out a cartography of new technologies to learn as much as I can about them. At the beginning, I interviewed Tim Berners Lee about the Worldwide Web. Since then, I have had many conversations with pioneers in the tech world and have been interested in how art and technology develop and function together. As new technologies are developed more rapidly, the cartography grows.

Technology has been a major vector of change. Berners-Lee invented the World Wide Web in 1989, and that changed so many things, not only for art but for all aspects of society. Over the last ten years at Serpentine, we started new experiments bringing artists together with technology. We created an entire department with five curators and a chief technology officer, and made exhibitions of video games. Today, the field of video gaming is bigger than the fields of music and cinema together. Many artists are working with video games as a broad building. It has also become very important for exhibitions and art institutions to address the environmental emergency. We appointed at Serpentine a curator of ecology and have constructed a whole department around that. Many of our projects at the Serpentine address questions of sustainability, of environment, of the extinction crisis. That came out of a dialogue with the artist Gustav Metzger.

In thinking beyond exhibitions, I realised that as Lina Bo Bardi, the visionary Brazilian Italian architect, said, ‘the insides are on the outside.’ With the museum it's very important that we don't just show art in an exhibition space behind doors, but that we go with art into society. The Pavilions we build every year at the Serpentine have no doors, they're in the park, like public art. Visitors can experience these pavilions and often stumble upon them.

Most recently, I curated an exhibition called WORLDBUILDING: Gaming and Art in the Digital Age at Julia Stoschek Collection, which took as its starting point the current prevalence of video games. Today, around 3 billion people—more than a third of the world’s population— play video games each year, making a niche pastime into the biggest mass phenomenon of our time, tendency rising. Many people spend hours every day in a parallel world and live a multitude of different lives. Video games might be to the twenty-first century what movies were to the twentieth century and novels to the nineteenth century. The exhibition examined various ways in which artists have interacted with video games and made them into an art form, including single-channel video works to site-specific, immersive, and interactive environments.

This exhibition highlighted how the creation of games offers a unique opportunity for worldbuilding: rules can be set up, surroundings, systems, and dynamics can be built and altered, new realms can emerge. As artist Ian Cheng often told me, at the heart of his art is a desire to understand what a world is. Now more than ever, the dream is to be able to possess the agency to create new worlds, not just inherit and live within existing ones. The research for this exhibition showed that the importance of video games will only grow. It will be fascinating to see how the exhibition and museum changes and develops alongside the ever-evolving role of video games themselves.

/ Hans Ulrich Obrist·Artistic Director of The Serpentine Galleries

![K팝 업계에도 '친환경' 바람…폐기물 되는 앨범은 '골칫거리' [연계소문]](https://img.hankyung.com/photo/202206/99.27464274.3.jpg)